dis/ability

by Stefania TavianoAbstract:

Partendo dalla definizione di disabilità delle Nazioni Unite, basata sul modello sociale in quanto definita come socialmente costruita e legata alle barriere sociali, metto in discussione la visione predominante della disabilità, basata invece sul modello medico che vede la disabilità come un limite, il risultato della menomazione di una persona. Termini discriminatori, come 'handicap' e 'disabile', continuano a essere applicati in molti contesti, tra cui l'istruzione e le leggi. Come studiosa di traduzione e come madre di un ragazzo di 11 anni con la sindrome di Down sono impegnata nella promozione della giustizia sociale, e contesto queste rappresentazioni delle persone con disabilità che, unite a discorsi discriminatori, possono giocare un ruolo centrale nel permettere o impedire a queste persone di godere dei diritti umani. La lotta contro le disuguaglianze sociali, portata avanti dalle organizzazioni nazionali e internazionali di persone con disabilità, è anche messa in scena e rappresentata da artisti disabili, che esprimono con forza la pluralità delle persone con disabilità e attraverso la loro arte diventano agenti della loro identità, rivendicando chi sono e interpretando la disabilità come diversità umana, piuttosto che come inferiorità.

In this entry, I address predominant views of disability, challenging discriminatory representations and discourses that see disability as the result of a person’s impairment, and which can play a central role in allowing or preventing these people from enjoying human rights. I will then show how though creativity artists with disabilities become agents of their identity by claiming who they are and by interpreting disability as human diversity, rather than inferiority.

Etymology:

Dis-ability is formed by the prefix dis-, meaning incapacity, and the word ability, meaning and involving power, strength. The term disability is thus an oxymoron in itself since the prefix denies the ability, a capacity inherent to the word itself, like all words formed by a negative prefix, such as dyslexic, dyscalculic, dysfunctional, do. The negation expressed by the prefix dis- is undeniable related to normative and ableist standards, that is to say what society at large, together with law, health and education systems, consider and value as ability, thus 'normal' and acceptable.

Problematization:

The United Nations defines disability as follows in Article 1 of the Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (2006): “persons with disabilities include those who have long-term physical, mental, intellectual or sensory impairments which in interaction with various barriers may hinder their full and effective participation in society on an equal basis with others” (UN, 2006, p. 4).

Such a definition is informed by the so-called social model of disability which frames disability as socially constructed and connected to social barriers preventing persons with disabilities from having access to a series of services, social contexts as well as human rights. Persons with disabilities, however, have been, and more often than not, continue to this day to be defined according to the medical model which sees disability as a limit, as the result of a person’s impairment and discriminatory terms, such as 'handicap', continue to be applied in different contexts, including law and education systems, in several countries.

The definition of persons with disabilities, as in the case of other social groups and categories, such as gender and race, in fact refers to people with a wide variety of physical and cognitive differences, who are nevertheless grouped in an apparently homogenous social class, and are subject to oppression while being socially and politically invisible (Garland-Thomson, 2005). The ways people belonging to minority groups, including migrants and asylum seekers, are categorised have a serious impact on their lives (Federici 2020, Taviano 2020) to the point that labelling practices contribute to the violation of their rights.

The WHO’s International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (ICF) aims to go beyond such views and further specifies that “disability is complex, dynamic, multidimensional, and contested” (WHO, 2011, p. 3) while encouraging a third model, a compromise beyond the dichotomy between the medical model and the social model. This is the bio-psycho-social model, which aims to take into account the multifaceted nature of disability and is framed as an “umbrella term for impairments, activity limitations and participation restrictions, referring to the negative aspects of the interaction between an individual (with a health condition) and that individual’s contextual factors (environmental and personal factors)” (WHO, 2011, p. 4).

Despite such changes in international organizations’ approach to disability, both the noun 'handicap' and the adjective 'handicapped' are key terms of the 1992 Italian legislation which has regulated the educational and social life of persons with disabilities before a recent decree law which has come into force in June 2024. The definition, according to the previous 104/1992 Law, paragraph 3, clause 1 reads as follows:

persona handicappata, colui che presenta una minorazione fisica, psichica o sensoriale, stabilizzata o progressiva, che è causa di difficoltà di apprendimento, di relazione o di integrazione lavorativa e tale da determinare un processo di svantaggio sociale o di emarginazione (handicapped person, someone who has a physical, psychic or sensorial impairment, either stable or progressive, which causes learning, relational difficulties or difficulties in terms of job integration and which can lead to social disadvantage or discrimination) (Repubblica Italiana, 1992).

Such a definition, which clearly identifies the person’s impairment as the only cause of social discrimination follows the medical model and continues to be used in official signs, documents and educational contexts despite the Italian Minister for Disabilities’ official statement on 15 April 2024 that the term 'handicapped' will be replaced with 'persons with disabilities' in all Italian legislation. Some schools, for instance, where the groups of special needs teachers are still defined as GLH or H (handicap workgroups) rather than GLO [Gruppo di Lavoro Operativo per l'inclusione - Operational Group for inclusion] as provided by the Law 66/2017, which has replaced GLHs with GLOs.

Similarly, the definition 'seriously handicapped' was used by British judges referring to British abortion legislation in 2021 when Heidi Crowter, a British woman with Down syndrome, and Máire Lea-Wilson, mother of a child with Down syndrome, went to court over the UK’s abortion law, and lost their case in the high court. The two women filed a case against the Abortion Act 1967, particularly the 24-week time limit for abortions except in the case of a “substantial risk” of the child being “seriously handicapped”. These women rightly claimed that such a law violates the respect for private life, as provided by article 8(1) of the European convention on human rights (ECHR), and that allowing pregnancy terminations up to birth if the foetus has Down syndrome is a clear instance of discrimination against persons with disabilities recognized by law.

Subversion:

In recent years national and international associations and organizations of persons with disabilities, as well as individuals, artists in particular, have been questioning and fighting against social labels and patterns of exclusion, stigmatizing them as defective on the basis of ability norms through activist campaigns. Thanks to these campaigns persons with disabilities become agents of their identity by claiming who they are and by interpreting disability as human diversity, rather than inferiority. Through their own experiences they show us that reinterpreting disability means questioning ableist rhetoric and standards of 'normality' against which these people are judged as unworthy citizens (Erevelles, 2011) while encouraging positive identity politics.

This is what disabled artists of the IN/Visible Disabled Women’s National Arts Collective, aimed to do, for instance, with the exhibition All The Women I Could Have Been, UK, August 2023.

https://www.littlecog.co.uk/invisible-exhibition-2023.html

These artists explore narratives about disabled women and their rights, the close connection between justice and arts movements while celebrating 'who we are'.

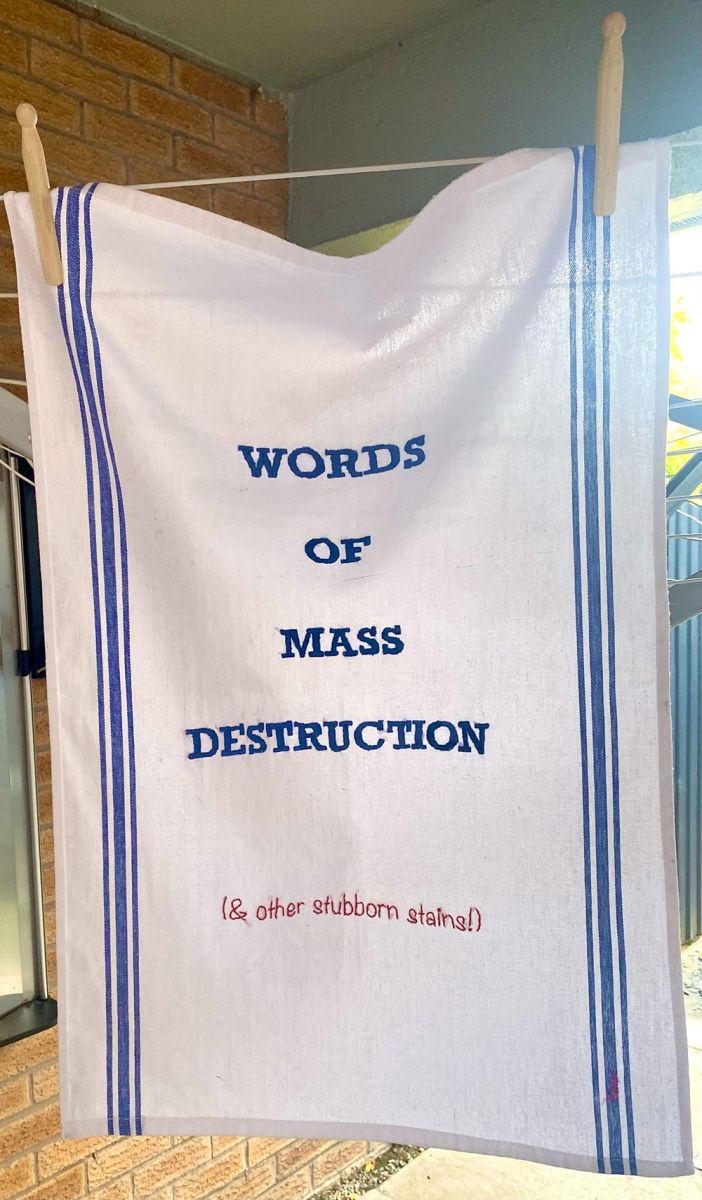

Here below you can see two of the works that were presented at the afore mentioned exhbition. They are respectively Caroline Cardus's, Background noise, and Honor Flaherty's, Words of Mass Destruction

and Other Stubborn Stains.

Caroline Cardus’s work focusses on creative activism. Starting from her own experiences as a disabled woman, Cardus’s text based, subversive and graphic style work delivers frank, darkly humorous and powerful messages about disability discrimination and diversity. Commenting her work Background Noise, she says: "My piece contains fragments that stayed with me over the years that were annoying, shocking, or funny. Some I sanded off or painted over, some are louder or quieter, but all contributed to questions of who I might be. The body I inherited, along with time and empowerment, gradually brought me the realisation that I couldn’t have been anyone other than the person I am now". Further info on the artist and her work at: | .png) (70 x 50 cm; mixed media on board) Courtesy of the Artist |

and Other Stubborn Stains. (Mixed materials) Courtesy of the Artist | .jpg) A stage and screen writer with a penchant for comedy and camp musicals, the artist describes the work Words of Mass Destruction and Other Stubborn Stains as: "It is a washing line textile art pieces depicting saying/quotes that were once said to me, over a life time, to deter or stamp on my dreams. It’s essentially about how words can hurt or heal".

|

Disabled performance artists similarly stage disability to promote social justice and persons with disabilities’ human rights, in the same way as organizations of persons with disabilities do for the safeguard of disability rights. Maysoon Zayid, an activist comedian, co-founder of the New York Arab-American Comedy Festival, has been advocating social justice for persons with disabilities throughout her career. She started with her performance at the 2013 Ted Women Conference in San Francisco, I got 99 problems, palsy is just one where she verbally and physically delivers her disability right from the title and the very beginning of the performance, which is known worldwide. She is also the founder of Maysoon's Kids, a scholarship and wellness program for disabled and wounded refugee children in the West Bank. Activism is at the centre of her performances, together with disabled performers, who aim to de-naturalise disability (Kuppers 2001: 26).

When introducing herself during her performance she does so by explaining the audience that rather being born this way, she got cerebral palsy because the gynecologist “cut my mom six different times in six different directions, suffocating poor little me in the process. As a result, I have cerebral palsy, which means I shake all the time. […] I'm like Shakira, Shakira meets Muhammad Ali.[1] Her body, rather than being hidden, becomes the focus of her ironic introduction of herself as a hybrid resulting from the encounter of the singer Shakira and the boxer Muhammad Ali. She makes her audience laugh while calling into question a whole series of prejudices about disability: she argues that hers is not genetic nor infectious, and she ironically denies the idea that a defective body might be the result of evil forces and curses.

The performance of disability by disabled artists, such as Zayid, who reveal the social nature of disability culture and ableist scripts through self-translation of their own bodies and identities is vital to fight against the pervasiveness of discriminatory social labelling. Those performances acquire a political value as key elements of the global movement for disabled rights and at the same time oblige us to address on our responsibility as able-bodied spectators and citizens.

Disability as a form of art, and different forms of art by persons with disabilities, remind us that the centrality of the disabled body, with its unique characteristics and human imperfections, is closely related and cannot be separated from a person’s value and identity, and that bodies contribute to who we are as human beings actively making choices within a social and political context. Furthermore, disability arts in many forms create spaces and environments where persons with disabilities can share and promote an awareness of disabled identities.

Turning disability upside Down

Resistant arts practices, such as the ones mentioned here, together with individual and collective social practices, and a new language about disability, can thus contribute to reversing dehumanizing practices by placing people’s identities at the centre (Taviano 2023, Taviano 2025). This is what activists, artists, particularly my 11-year-old son with Down syndrome have taught me, a lesson which I would like to share and conclude by encouraging all of us to do the same: that is turning upside Down our understanding of dis-ability(ies), thus of human diversity. As Sammy Basso, the longest living survivor of a rare rapid-aging disease, progeria, who has recently died at 28, has written in a letter for his funeral: “we are all disabled because we are all different”.

[1] This and all citations from the transcript of Zayid’s Ted Talk, I got 99 problems… palsy is just one are available at https://www.ted.com/talks/maysoon_zayid_i_got_99_problems_palsy_is_just_one/transcript.

Discussion:

- Do we pay attention to the way we define persons with disabilities and how they are defined by people around us?

- How do we interact with them? Do we exclusively offer to help them as people in need?

- How can each of us contribute to challenge discriminatory representations of persons with disabilities in the workplace and everyday life?

References/Further Readings:

- Erevelles, Nirmala. (2011) Disability and Difference in Global Contexts, Enabling a Transformative Body Politic. London: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Garland-Thomson, Rosemarie. (2005) Feminist Disability Studies. Signs, 30:2, Winter, pp.1557-1587.

- Kuppers, Petra. (2005). Bodies, Hysteria, Pain, Staging the Invisible. In Sandhal, Carrie & Philip Auslander (eds.) 2005. Bodies in Commotion. Michigan: University of Michigan, pp. 147-162.

- Taviano, S. (2023). Translating migration: art installations against dehumanizing labelling practices. Translating Otherness: Challenges, Theories, and Practices. Special issue. Languages, 8(3), 1-14.

- Taviano, S. (2025) “Translation, migration and hospitality: Migrant artists as agents of translation”. In Brigid Maher, Loredana Polezzi & Rita Wilson (eds.) The Routledge Handbook of Translation and Migration. London and New York: Routledge, pp.205-220.

- United Nations (2006) Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities.

Further reading:

- Grue, Jan (2022). I live a life like yours. A Memoir. Pushkin Press.

How to cite this entry:

Taviano, S. (2024). Dis/ability. In Other Words. A Contextualized Dictionary to Problematize Otherness. Published: 04 November 2024. [https://www.iowdictionary.org/word/disability, accessed: 06 March 2026]