patriotism

by Olena SemenetsAbstract:

Ukrainian. У цій словниковій статті розглядаються зміст поняття ‘патріотизм’, деякі маніпуляційні дискурсивні практики використання слів патріот, патріотизм, а також способи нейтралізації таких патогенних маніпуляційних практик засобами творів масової культури.

This entry examines the meaning of the concept of ‘patriotism’, some manipulative discursive practices of using the words patriot, patriotism, and ways to neutralize such pathogenic manipulative practices employing mass culture works.

Etymology:

The word patriot comes from the French language. French patriote (‘devoted son of the motherland, defender of its interests’) is based on Middle Latin patriōta, which is related to Greek πατριώτης ‘fellow countryman’ (from πατρίς ‘fatherland; country’, from πάτριος ‘paternal, inherited from parents’, from πατήρ (genitive πατρός) ‘father’).

In French, the word patriote acquired a special sound during the revolution of 1789–1793.

Cultural specificity:

Every culture has a special understanding of the concept of ‘patriotism’, which is historically formed and over time can change, develop, acquire a different interpretation.

The Cambridge English Dictionary reveals that patriotism is ‘the feeling of loving your country more than any others and being proud of it’ and patriot is ‘a person who loves their country and, if necessary, will fight for it’.

According to the Academic Dictionary of the Ukrainian Language, patriotism is ‘love for one’s motherland, devotion to one’s people, readiness for sacrifices and feats for them’ (патріотизм – це «любов до своєї батьківщини, відданість своєму народові, готовність для них на жертви й подвиги»).

In addition to cultural and historical specificities, it is also important to take into account the philosophical and ethical meaning of the concept of ‘patriotism’, which can vary greatly in different paradigms.

In recent times, since the 1980s, there has been a philosophical discussion about the moral aspects of patriotism. This was due, in part, to the revival of communitarianism, which came in response to the individualistic, liberal political and moral philosophy epitomized by John Rawls’ Theory of Justice (1971). It was also due to the resurgence of nationalism in several parts of the world (Primoratz, 2020).

In particular, A. MacIntyre argues the point that patriotism is a central moral virtue, the bedrock of morality (MacIntyre, 1984). Other philosophers emphasize certain restrictions and specifications in the meaning of this concept (Baron, 1989; Nathanson, 1989; Primoratz, 2002).

In the aspect of moral philosophy, it is important to find out how the concept of patriotism correlates with the concepts of universal justice and common human solidarity, respect for other countries and peoples.

Different theories and traditions of patriotism can acquire ambiguous qualifications in terms of moral philosophy. There are five types of ‘patriotism’ distinguished in the Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy, taking into account the moral status of the phenomenon (Primoratz, 2020): extreme patriotism, robust patriotism, «moderate patriotism» (Nathanson, 1989) or «liberal patriotism» (Baron, 1989), deflated patriotism, and ethical patriotism.

Problematization:

The word patriot signifies a person who loves his/her country, identifies oneself with it, and is ready to boldly defend its interests.

However, over the centuries, even within a certain cultural tradition, the meaning of the word has not remained unchanged. This word, which refers to the highest social feeling, has been involved in heated debates, political battles, and ideological confrontations.

The online edition of the Merriam-Webster Dictionary in the «Words At Play» section notes that the word patriot was not always perceived positively. The word came to the English language in the 16th century. But the positive halo of the word underwent certain transformations under the influence of the events of religious and political schism in Western Europe in the 16–17th centuries, the strife among fellow countrymen, especially among those of the Protestant and Catholic faiths (‘Patriot’ Hasn’t Always Been Positive, n.d.).

«Another effect of the tumultuous times was the development of a derogatory use of patriot to refer to hypocritical patriots: people who claimed devotion to one’s country and government but whose actions or beliefs belied such devotion. This ultimately led to the discrediting of the loyalty and steadfastness associated with the word patriot» (Patriot, n.d.).

The famous aphorism «Patriotism is the last refuge of a scoundrel» belongs to Dr. Samuel Johnson, an English writer of the Enlightenment, literary critic, editor, and lexicographer. James Boswell, a biographer of Dr. Samuel Johnson, describes the circumstances of uttering the aphorism (it took place at the Literary Club on April 7, 1775): «Patriotism having become one of our topicks, Johnson suddenly uttered, in a strong determined tone, an apophthegm, at which many will start: “Patriotism is the last refuge of a scoundrel.” But let it be considered that he did not mean a real and generous love of our country, but that pretended patriotism, which so many, in all ages and countries, have made a cloak for self interest» (Boswell, 1830, p. 269).

Dr. Samuel Johnson, a Tory supporter, observed that the term was actively used by the Whig opposition party as an instrument of political struggle.

A year before this aphorism was formulated, Samuel Johnson wrote an essay-pamphlet «The Patriot. Addressed to the Electors of Great Britain» (1774), in which he distinguished between true patriotism driven by a sincere love for the country and feigned patriotism that was a manifestation of political demagoguery. Dr. Johnson warns against possible «false appearances» of patriotism: «Let us take a patriot, where we can meet him; and, that we may not flatter ourselves by false appearances, distinguish those marks which are certain, from those which may deceive; for a man may have the external appearance of a patriot, without the constituent qualities; as false coins have often lustre, though they want weight» (Johnson, 1913).

Thus, there are significant differences not only in the philosophical and ethical concepts of patriotism but also in the discursive practices of using the word at different times, in different historical and political circumstances, and in different countries.

For centuries, the word patriotism has referred to feelings during the highest elevation of the moral strength of nations, especially in times of war and great historical trials. But at the same time, the manifestations of feigned, phony, and profit-seeking patriotism were condemned, cf. du patriotisme d’antichambre (French), patrioteer (English), ура-патриот, квасной патриот (Russian). In essence, these lexical items denote the phenomenon of quasi-patriotism (pseudo-patriotism) and at the metadiscursive level mark the practices of manipulating the feelings and consciousness when appealing to true moral values for political gain.

Consequently, the main problem is to reveal the degree of sincerity of the subject, which demonstrates patriotic feelings. After all, the powerful emotional charge and positive evaluation of these words give the speaker a reason to «rise to the top» in communication and, accordingly, to embrace the position of dominance in the discourse.

So, just how sincerely are the words patriot, patriotism used in contemporary discursive practices, in particular in official, political, and media discourses? How can these words be a tool of discursive domination and, in this regard, a mean of the formation of manipulative discursive practices?

Communication strategies:

The right to «greater patriotism» can be «assigned» by any party in the political struggle.

In the 18th century, Dr. Johnson accused the opposition, the Whig Party, of playing a dishonest game with the notion of ‘patriotism’. Characteristically, in the first edition of his Dictionary (1755), Samuel Johnson defined the word patriot as ‘one whose ruling passion is the love of his country’, but in the fourth edition (1773), substantially revised, Dr. Johnson adds: ‘It is sometimes used for a factious disturber of the government’ (Quotes on Patriotism, n.d.).

However, as history proves, most often the dominant role in the discourse and the position of «true patriots» is secured by a current government in a country.

Throughout the whole history of humanity, the authorities always heavily employed the concept of ‘patriotism’ as a means of consolidating the society during times of escalation of internal political and social tensions, or an external armed and information conflict. Accordingly, the opposition and dissidents that disagreed with the government’s politics were labeled as traitors, non-patriots.

This phenomenon can also be observed in modern political discourses of various countries.

The President of Turkey Recep Erdoğan called his fellow citizens who doubted the soundness of his government’s actions, traitors.

Croatian writer Slavenka Drakulic was forced to leave for Sweden in the early 1990s, when the war broke out in the Balkans, due to constant accusations of lack of patriotism.

In contemporary Russia, the musician Andrey Makarevich who supported the Ukrainian Euromaidan and the sovereignty of Ukraine is being accused of antipatriotism.

Donald Trump, who desperately refused to admit his defeat in the US presidential election, addressed his supporters who took part in the violent protests and storming of the Capitol on January 6, 2021, as «great patriots»: «These are the things and events that happen when a sacred landslide election victory is so unceremoniously & viciously stripped away from great patriots who have been badly & unfairly treated for so long. Go home with love and in peace. Remember this day forever!» Trump wrote on his Twitter account (but the social network immediately blocked the opportunity to repost and like this post).

.png)

.png) | China’s autocratic government, seeking to establish tight mainland control over Hong Kong, has cut the share of directly elected legislators from 50% to 22% and will require that they are vetted for «patriotism». According to The Economist, it is the culmination of a campaign to squash liberty in the territory. Censorship is on the rise, and Hong Kong’s judiciary and regulators will face pressure to show their fealty to China. |

The hierarchical position of political elites – both in authoritarian and democratic countries – is used as a means of combating criticism, dissent, and opposition. Manipulating the concept of ‘patriotism’ allows the authorities to speak from the standpoint of moral superiority and gravitas. Unfounded accusations of ideological opponents and labeling them (as non-patriots, traitors) are common techniques of discursive abuse of power.

In Ukraine, during the presidency of Petro Poroshenko, the practice of appealing to patriotism as a means of protecting the positions of the acting government was widespread.

A prominent example was the media clash of Ukrainian ‘Porokhobots’ and ‘Zradophiles’.

Porokhobots (порохоботи) is a term derived from then-President Petro Poroshenko’s nickname Porokh and the word bot. It is a derogatory name for Poroshenko’s advocates and supporters.

Zradophiles (зрадофіли, from zrada – ‘treason’) is a disparaging term for people who criticized the government’s actions and actively discussed the topic of «treason» of Ukrainian authorities.

The semantics of those terms a priori carry a negative assessment. The use of such labels immediately deprives the person in question of equal status in discursive interaction, and denies the possibility of being objective and impartial.

Besides, the hybrid information war waged by Russia against Ukraine uses another discursive practice that mimics the true Ukrainian patriotic discourse. This is a kind of covert information aggression: «patriotism» acts as a disguise for spreading destructive criticism of the acting government.

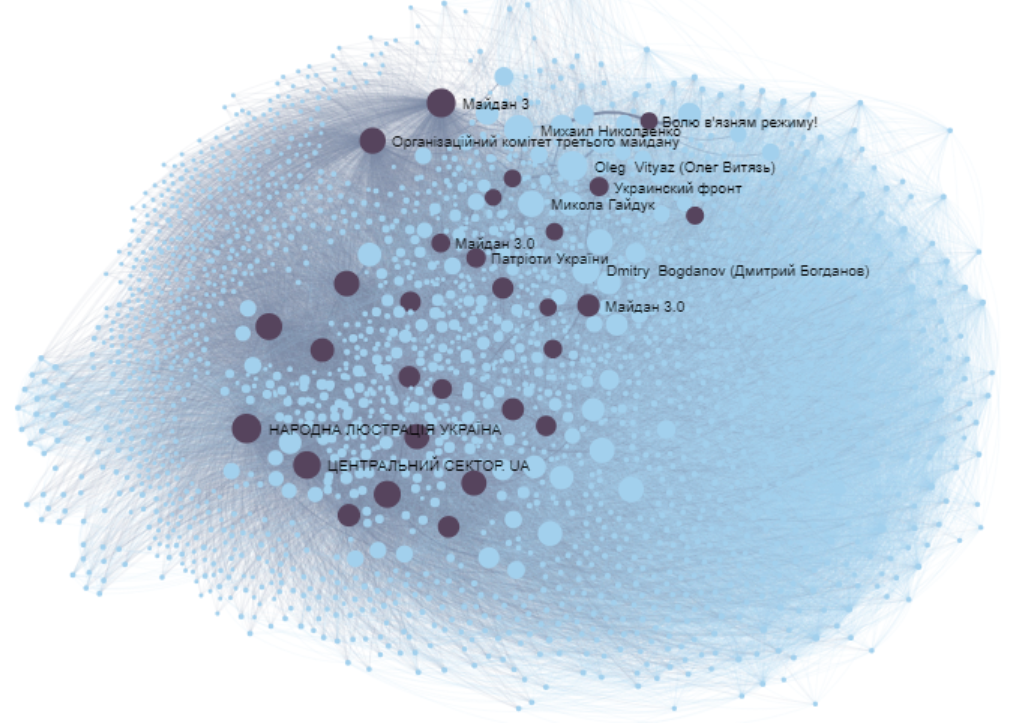

The journalists of the Ukrainian online media Texty.org.ua in October 2016 announced the discovery of an organized troll network consisting of approximately 2000 Facebook users which were led from the territory of the Russian Federation. Hiding behind patriotic Ukrainian slogans, these groups spread calls for protests and a coup d’état in Ukraine. In a piece called The Troll Network (Ukrainian: Тролесфера), the authors presented a visual model of the ‘Troll Galaxy.’ |  |

Back in 2015, Adrian Chen wrote for the New York Times about similar tactics of Russian trolls in the US who posed as patriots on the web. According to Chen’s observations, such trolls favored the format of Facebook posts with numerous photos of the American flag and phony patriotic statements mixed with constant criticisms and insults to President Barack Obama (The Agency).

Such projects are carried out from outside the country as a means of psychological and information warfare.

Subversion:

The biggest loss for the civil consciousness in discursive practices of the abuse of power is the erosion of the meaning of the concept of ‘patriotism’. The notion loses its scope of absolute morality and becomes a tool of condemning the undesirables or excuses.

Irony, satire, and sarcasm can be quite effective «medication» against manipulating the concept of ‘patriotism’. Those rhetorical techniques can neutralize the pathogenic potential of manipulative discursive practices.

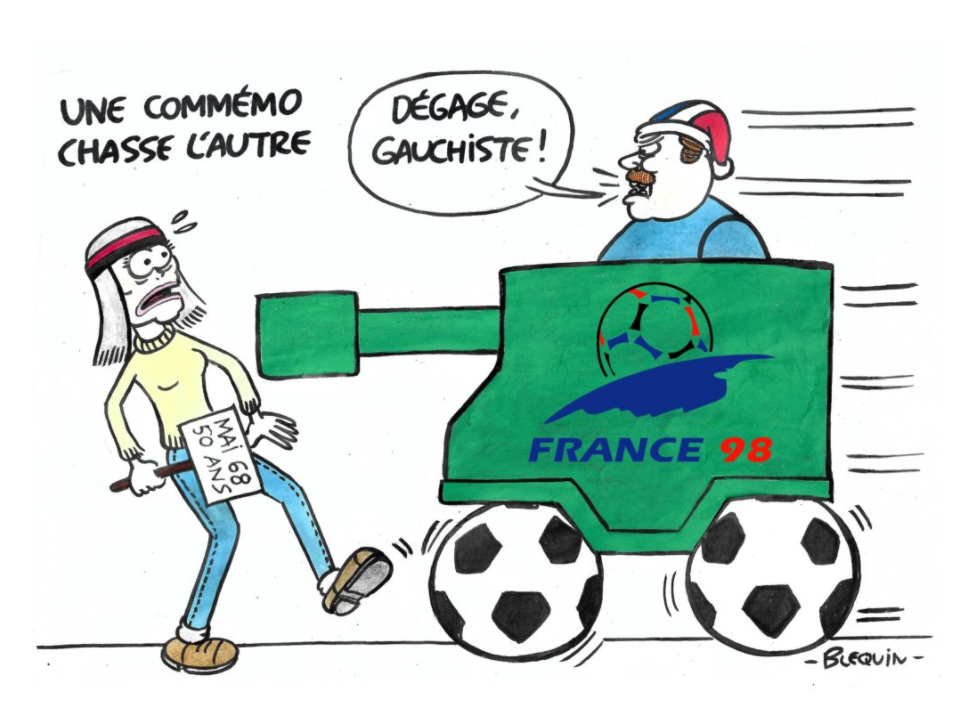

| French cartoonist and satirist Benoît Quinquis (known as Blequin) draws attention to the striking contrast between the violent patriotic feelings of football fans and the socio-political problems, including racism, that need to be addressed immediately in France: «…as if we had any reason to be proud to be French at the moment! French footballers must be terrible scoundrels if they are proud to represent a country that treats refugees like rubbish!» («…comme si on avait une quelconque raison d’être fier d’être français en ce moment! Les footballeurs français doivent être de fieffées crapules s’ils sont fiers de représenter un pays qui traite les réfugiés comme des détritus!») |

Political satire or banter can reveal the manipulative essence of pseudo-patriotism.

In 2016, the Russian rock band «Neschastny Sluchai» (Russian: «Несчастный случай», literally «Unfortunate accident») released a video for the song «Patriot», where musicians ridicule the images of patrioteers (ура-патриоты, квасные патриоты). In the video, the singers appear in clownish «patriotic» images that have been circulated in the media: a Cossack in a sheepskin hat with a whip, an accordionist in a cap decorated with a carnation, a biker with a contrabass-balalaika, a sports fan in clothes with pro-Russian symbols. «All of these characters can be true patriots if they are not only engaged in rhetoric but also work for the good of the Motherland,» said the front man Alexey Kortnev.

Video: Патриот (клип)

Discussion:

So, at this stage of the discussion, the following conclusions can be drawn.

Patriotism is not only conservatism and a focus on the historical past. It is openness to innovations and hard work for the prosperity of the native land.

Patriotism must be sincere and it must be of the highest value, but not perform instrumental functions as a means of manipulation to achieve political gain.

Patriotism must be based on respect for other peoples, as well as for one’s compatriots, even if they think otherwise.

References/Further Readings:

‘Patriot’ Hasn’t Always Been Positive. (n.d.). Merriam-Webster. https://www.merriam-webster.com/words-at-play/word-history-patriot

Baron, M. (1989). Patriotism and ‘Liberal’ Morality. In D. Weissbord (Ed.), Mind, Value, and Culture: Essays in Honor of E. M. Adams, (pp. 269–300). Atascadero: Ridgeview Publishing Co. Reprinted with a postscript in Primoratz, I. (Ed.), 2002.

Boswell, J. (1830). The Life of Samuel Johnson, LL.D. London: J. Sharpe; New York: W. Jackson.

Johnson, S. (1913). The Patriot. Addressed to the Electors of Great Britain. The Works of Samuel Johnson, vol. 14, 81–93. Troy, New York: Pafraets & Company.

MacIntyre, A. (1984). Is Patriotism a Virtue? (The Lindley Lecture). Lawrence: University of Kansas. Reprinted in Primoratz, I. (Ed.), 2002.

Nathanson, S. (1989). In Defense of ‘Moderate Patriotism’. Ethics, 99, 535–552. Reprinted in Primoratz, I. (Ed.), 2002.

Patriot. (n.d.). Merriam-Webster.com Dictionary. https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/patriot

Primoratz, I. (2002). Patriotism: A Deflationary View. Philosophical Forum, 33, 443–458.

Primoratz, I. (2020). Patriotism. In E. N. Zalta (Ed.), The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. https://plato.stanford.edu/archives/win2020/entries/patriotism/

Primoratz, I. (Ed.) (2002). Patriotism. Amherst: Humanity Books.

Quotes on Patriotism. (n.d.). The Samuel Johnson Sound Bite Page. http://www.samueljohnson.com/patrioti.html

How to cite this entry:

Semenets, O. (2022). Patriotism. In Other Words. A Contextualized Dictionary to Problematize Otherness. Published: 28 March 2022. [https://www.iowdictionary.org/word/patriotism, accessed: 11 March 2026]